Hunted fish is my preferred food. And yet, having arrived at this advanced and supposedly sensible stage of life, I have never actually hunted a fish and then eaten it. Still, I have always been told—mostly by friends who are equally innocent of the act—that fish only truly tastes good when one has hunted it oneself.

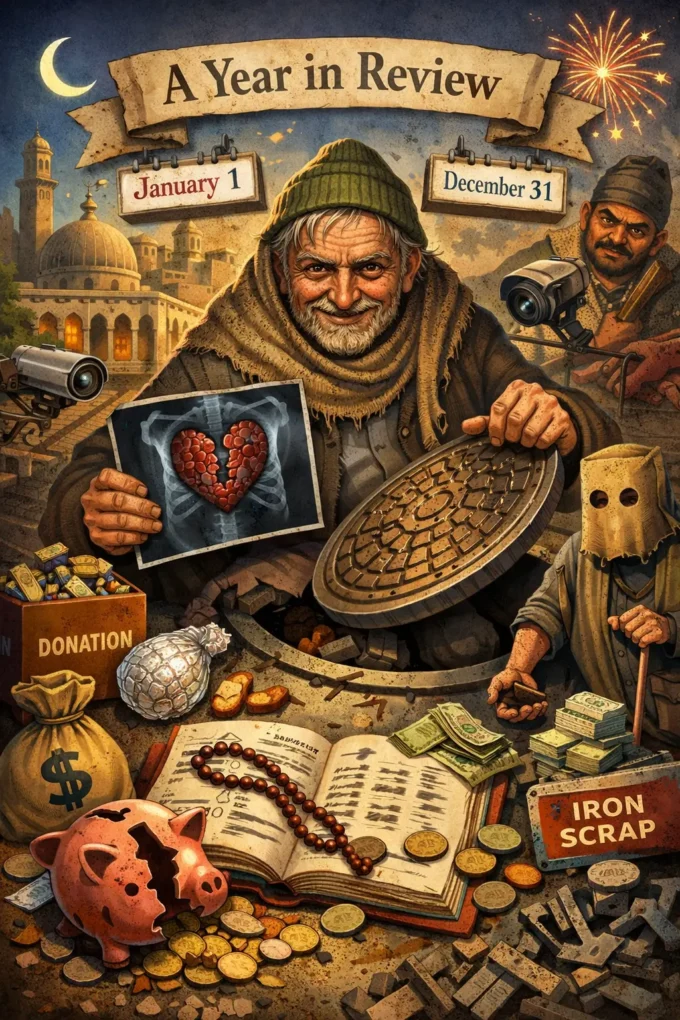

I should clarify that this is not a moral failing but a physical condition. I am, by all reasonable standards, a normal human being. Nevertheless, the mere mention of water—and cold water in particular—produces such an allergic reaction in me that every hair on my body rises in protest. Consequently, whenever the desire for fish arises, I go to the market and ask the fishmonger only one carefully considered question:

“My good man, is this hunted fish, or did it come without effort?”

The fishmonger, who knows my temperament well, never hesitates.

“Sir,” he says, “this was hunted early this morning from the calm waters of the Pacific Ocean.”

This declaration, delivered with confidence, functions for me as a certificate of authenticity. Reassured, I immediately purchase slightly more than a quarter kilo—ten or twenty grams extra, to be precise—of this calm-water, Pacific Ocean fish. I take it home, fry it, and eat it while firmly imagining that I am consuming something hunted.

One evening, while sitting with friends, the conversation turned—as conversations eventually do—toward food, and then specifically toward fish. I asked what seemed to me a reasonable question:

“Is hunted fish actually more delicious?”

They fell silent. First came surprise, then unease, and finally consultation. They began to discuss what the simplest answer to such a difficult question might be. Several opinions were offered, including one that struck everyone as especially logical: we should ask the fish itself. That way, there would be no doubt, no speculation—only a reliable, firsthand account.

The method, I conceded, was both sensible and scientific. The difficulty lay elsewhere. Which fish, after all, could be trusted?

Someone proposed a fish from the Indus River. I rejected the suggestion immediately. The Indus flows through Gilgit, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and Sindh; a fish that has tasted water at so many stops cannot be expected to give an impartial answer. We needed a fish that had lived its entire life in a single body of water—patient, restrained, content with simple sustenance, and uncorrupted by travel.

“So what do we do?” a friend asked, hesitantly.

“We go to the Pacific Ocean,” I said.

“The Pacific Ocean?” he replied, his mouth still open after the question.

“On foot,” I said, then corrected myself. “I mean—not that far. It’s quite close.”

“Close? The Pacific Ocean?”

“Not that one. Kahlanwalah. I’ve heard that just beyond it there’s a lake called the Pacific Ocean. That’s the one.”

At this point, their expressions—already open with disbelief—widened further. None of them recalled reading about Pakistan’s local Pacific Ocean in any Pakistan Studies textbook. I reassured them that they were still students of the world and need not worry about what they did not yet know. I had also heard, I added, that the lake’s water was not only sweet but remarkably good for digestion—so effective that if one ate radish parathas and drank from the lake, the consequences would be immediate.

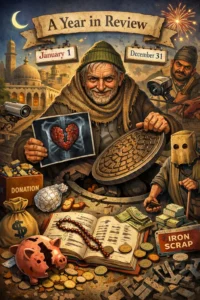

Three days later, guided by our devotion to inquiry and research, we set out from our homes on motorcycles. Traveling as a small caravan, maintaining an air of scholarly dignity and engaging in earnest academic discussion, we reached Kahlanwalah around eleven in the morning.

At the bus stand stood the Kahlanwalah Intercontinental, where, under the benevolent glow of disco music, the local business community was deeply engaged in financial transactions involving playing cards. We paused briefly for tea and observed this commerce with interest. After congratulating the winners and encouraging the losers not to lose heart, we moved on. The expressions of the defeated businessmen were, frankly, too painful to witness.

We asked a local resident for directions to the lake. He pointed the way and added that motorcycles could go no further; the remainder of the journey would have to be made on foot. Since we had left home in pursuit of knowledge—and since our resolve rivaled the Himalayas—we parked our bikes near a shed and set off eagerly toward the lake known as the Pacific Ocean.

After two to two-and-a-half hours of walking, we arrived at the lake which, according to our informant, was “very close to Kahlanwalah.” By then hunger had made itself known, and thirst had begun to ask difficult questions. Still, when we reached the destination, it was indeed a lake.

Water from nearby leather factories flowed into it from several directions, resembling rivers emptying into a vast sea. The first thing we noticed was the smell—extraordinary, aggressive, unmistakable. Breathing was not merely difficult; it was impractical.

“If the water smells like this,” one friend said, “what must the fish be like?”

“Tell me something,” another asked, struggling to control his breath. “Who told you about this lake they call the Pacific Ocean?”

I explained that once, when a pressure-cooker repairman had visited our neighborhood, I had spoken to him about Pacific Ocean fish. He had then mentioned this lake and assured me that its fish was very delicious.

“Forget that,” someone said. “First answer this—can any fish even survive in this water?”

I suggested that instead of speculating, we should simply ask the fish. After all, the final and most reliable opinion could only come from one that lived there.

This suggestion—reasonable and scientific though it was—provoked unexpected hostility. Muttering curses about my past, my research, and my entire existence, my companions abandoned me and walked away.

I waited for a while, hoping a fish might appear. When it became clear that nothing would, I consoled myself and began the journey back. Upon reaching the city, I went straight to the market and asked the fishmonger, once again:

“My good man, is this hunted fish, or did it come easily?”

Leave a comment